| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

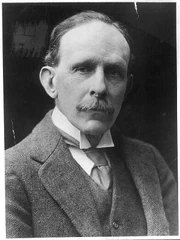

Robert Arthur James Gascoyne-Cecil, 5th Marquess of Salisbury, KG, PC (27 August 1893 – 23 February 1972), known as Viscount Cranborne from 1903 to 1947, was a British Conservative politician. Initially elected to the House of Commons in 1929, Salisbury was summoned to the House of Lords in 1941, becoming the leader of the Conservative Party in that house until 1957. He also served in several different offices during the 1940s and 1950s. He played an important role in the selection of Harold Macmillan to the office of prime minister in 1957.

In later years, the imperialist Salisbury was quite vocal in his support for white-ruled governments in Africa.

More trivially, he went by the nickname "Bobbety", and had a noticeable speech impediment which caused him to pronounce the letter "r" like the letter "w".

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil in The War That Came Early[]

Viscount Cranborne was part of the group of disgruntled MPs gathered together by Ronald Cartland to oppose first Neville Chamberlain and then Sir Horace Wilson after Britain allied with Germany in mid-1940.[1]

Cranborne was something of a voice of reason among the group. In 1941, after Alistair Walsh reported his meeting with General Archibald Wavell did not go as well as hoped, Cranborne pointed out that if Wavell had listened to Walsh at all, the general might face the possibility of being hit and killed by a car just as Winston Churchill had been.[2]

Wilson soon went too far, however, arresting political enemies, including Walsh.[3] The military acted, arresting Wilson and his Cabinet.[4] Cranborne joined Cartland in the new government.[5]

Cartland used his position to send Walsh to Egypt in the Fall of 1941, where British troops, unable to fight Germany on the continent, instead engaged Italian forces from Libya.[6]

When Walsh was wounded in North Africa, Cartland and Cranborne paid a visit to the sergeant, and discussed the situation both at home and abroad. Cranborne conceded, and Cartland agreed, that if the war went well, then the coup would be forgiven, but if the war continued to go badly, then the military government would be vulnerable. They also told Walsh that most of the members of the Wilson government had been exiled to diplomatic assignments in distant backwaters, as continued imprisonment was illegal. After Walsh warned the two aristocrats that it was the lower level "spear-carriers" they needed to watch out for, Cartland wondered aloud how Walsh was not an officer. Cranborne further opined that Walsh's coal-mining roots should not hold him back, something Cartland wholeheartedly embraced. When Walsh suggested Cartland and Cranborne sounded more like members of Labour, Cartland pointed out that Labour knew that Hitler was the true enemy.[7]

After Hitler was toppled in April 1944, and a ceasefire was reached in Europe, Cartland, Cranborne and several other MPs met with Walsh upon his return to London in the Lion and Gryphon pub. Over a round of drinks, they discussed the likely outcome of the situation in Europe and the ongoing war in the Pacific. When Cartland pointed out that Britain's possession over its overseas territories was more tenuous thanks to the war, Cranborne predicted that the people calling for independence would be at each other's throats if the British withdrew.[8]

Literary comment[]

While Harry Turtledove correctly introduces "Bobbety" Cranborne in The Big Switch, the character is called "Bobbety Cranford" in subsequent volumes.

References[]

- ↑ The Big Switch, pg. 342, HC.

- ↑ Coup d'Etat, pg. 94, HC.

- ↑ Ibid., pg. 134.

- ↑ Ibid., pgs. 153-154.

- ↑ Ibid., pg. 188.

- ↑ Ibid., pgs. 309-312.

- ↑ Two Fronts, pgs. 174-176.

- ↑ Last Orders, pgs. 371-382.

| Titles and Succession | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||