The Thach Weave (also known as a Beam Defense Position) is an aerial combat tactic developed by naval aviator John Thach and named by James H. Flatley of the United States Navy soon after the United States' entry into World War II.

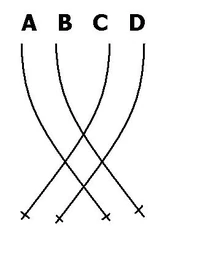

An example of the Thach Weave: An enemy following planes A or B is vulnerable to attack from C and D.

It is a tactical formation maneuver in which two or more allied planes would weave in regularly intersecting flight paths to lure an enemy into focusing on one plane, while the targeted pilot's wing man would come into position to attack the pursuer.

Thach had heard, from a report published in the September 22, 1941 Fleet Air Tactical Unit Intelligence Bulletin, of the Japanese Mitsubishi Zero's extraordinary maneuverability and climb rate. Working at night with matchsticks on the table, he eventually came up with what he called "Beam Defense Position", but which soon became known as the "Thach Weave". It was executed either by two fighter aircraft side-by-side or by two pairs of fighters flying together. When an enemy aircraft chose one fighter as his target (the "bait" fighter; his wingman being the "hook"), the two wingmen turned in towards each other. After crossing paths, and once their separation was great enough, they would then repeat the exercise, again turning in towards each other, bringing the enemy plane into the hook's sights. A correctly executed Thach Weave (assuming the bait was taken and followed) left little chance of escape to even the most maneuverable opponent.

Thach Weave in Days of Infamy[]

The Thach Weave had been taught to the US Navy pilots before their first attempt to retake the Hawaiian Islands from Japan in 1942.[1] Lt. Jack Hadley, a survivor of that fiasco himself, stressed its importance during his lectures of the Flight Schools; however he believed it to be far from perfect.[2]

Hadley described how a four-plane element of two pairs would attract a Zero and the sharp turn of the attacked aircraft towards the other pair would alert them. This would also place them in a position to fire on the Japanese even though Wildcats were less maneuverable. It took tight teamwork but gave American pilots a chance.[3]

References[]

- ↑ End of the Beginning, pg. 89.

- ↑ Ibid., pg. 90.

- ↑ Ibid.

| |||||||||||||||||